1794-c.1804

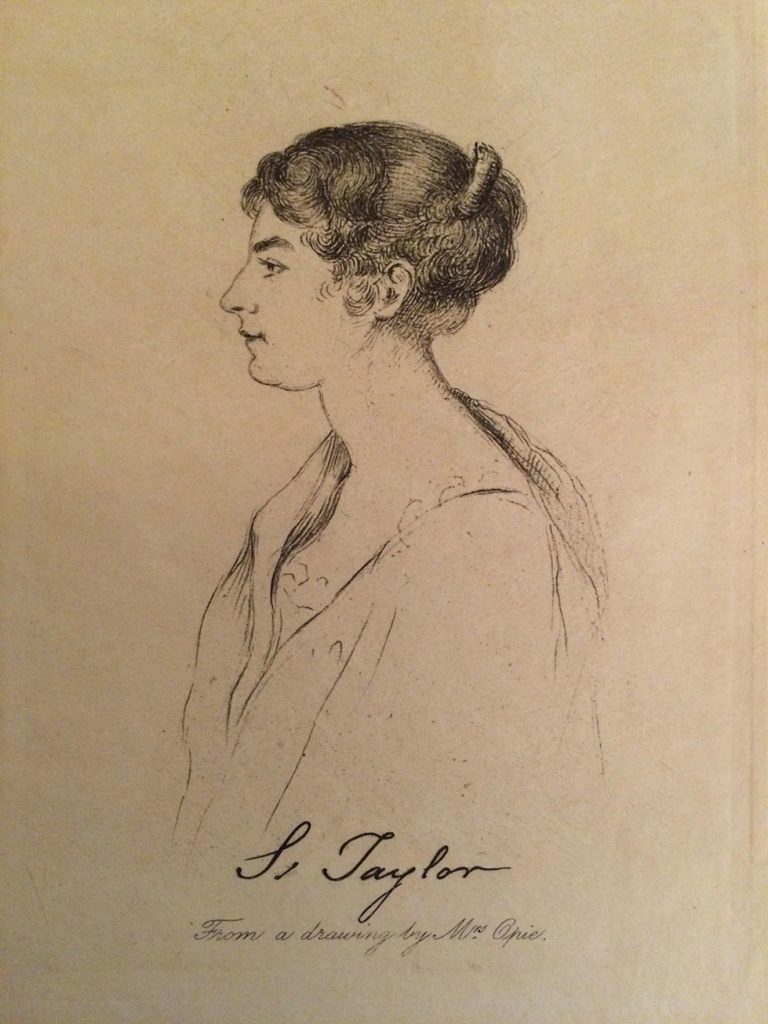

Opie’s extant correspondence with Susannah Cook Taylor (1755-1823) spans an important professional period of the author’s life, beginning as it does with her first trip to London after meeting William Godwin (1794) and concluding just prior to the publication of her second novel, Adeline Mowbray (1805).1

During these years the author also met and married the painter John Opie, and moved from Norwich to London. The letters are rich in allusion to prominent writers, actors, politicians, and artists, and Opie records her impressions with characteristic intelligence and humor.

Named Norwich’s “Madame Roland” by Sir James Mackintosh, Taylor held weekly salons that brought together progressive thinkers from across the region. Taylor’s father-in-law, John Taylor, was one of the first of the Warrington Academy tutors and a Unitarian theologian. Taylor’s husband, also John, earned his living as a wool merchant, but was also a prolific poet and song writer, penning both hymns and

the radical anthem “The Trumpet of Liberty.” 2 The Taylor parlor had been the center of intellectual life in Norwich for decades. Anna Letitia Barbauld was a frequent guest, as was her brother John Aikin. In addition to literary and professional ties, the Cooks and the Taylors had intermarried with the Martineaus and the Rigbys, two East Anglian families notable for their intellectual endeavors during the period.3

In a letter to Mary Wollstonecraft written in 1796, the still unmarried Amelia Alderson describes Taylor as “the sharer of my thoughts from childhood to the present moment.”4 Although only fourteen years older, Taylor had assumed a maternal role in her young friend’s life after the death of Mrs. Alderson in 1784, and finished the progressive education that Opie’s mother had begun. While there are fifteen extant letters from Opie to Taylor, none of the latter’s responses have survived. Nonetheless, it is possible to get some sense of Taylor’s influence on Opie from other correspondence. Taylor, like many Unitarian educators, saw sociable conversation as a vehicle of education; in a letter to her daughter, Sarah, she recommends “a little study and a little literary talk; from both of them you may always be gaining curious and critical information.” 5

Susannah Taylor prepared her children for professional careers, daughters as well as sons; she encouraged them to study Latin, Italian and French, and to read widely in both ancient and contemporary writers. In another letter to Sarah,

she advises her to read the poetry of Boileau and Pope, as well as the abolitionist writings of Wilberforce: “The character of girls must depend upon their reading as much as upon the company they keep. Besides the intrinsic pleasure to be derived from solid knowledge, a woman ought to consider it as her best resource against poverty.” 6 Acknowledging that a writing career was a viable profession for women, Taylor was particularly interested in cultivating good writers as well as productive ones: “Nothing can operate more powerfully against the attainment of excellence in every species of composition, than the indiscriminate praise and false tenderness which prevent those writers who are capable of higher degrees of improvement from endeavouring sedulously to aim at greater perfection, or which lead those who are incapable to trouble the public at all.” 7

A woman of strong character and opinions, Taylor was universally celebrated for kindness and humor. James Mackintosh praised her correspondence in particular: “I know the value of your letters. They rouse my mind on subjects which interest us in common: friends, children, literature, and life. Their moral tone cheers and braces me. I ought to be made permanently better by contemplating a mind like yours . . . Your active kindness is a constant source of cheerfulness.” 8 It appears that Opie was fortunate indeed in her mentor; Susannah Taylor was a woman capable of providing guidance to a young girl thrust prematurely into the role of adult, particularly when that girl had literary leanings, as the young author clearly did.

Although the only published work that can definitively be attributed to Taylor is a biographical tribute to Opie that appeared in The Cabinet in 1807,

her biographer and great-great-granddaughter, Janet Ross, declared that she “possessed the pen of a ready writer.” 9 Ross supports this claim primarily through transcriptions of Taylor’s correspondence; the letters are funny, self-deprecating, and witty. Full of anecdotes, poetry, and narrative devices, they are in many ways like Opie’s. In one letter Taylor remembers with pleasure visiting London: “I have seen the most excellent actors, I have heard the

most eminent musicians, I have associated with the most ingenious and cultivated people, and the ideas I have acquired from them are treasured up for ever in my mind.”10 Taylor values these visits as a way of improving her judgment through experience but she also exalts the importance of self-reflection and retreat from the social.

Opie stayed in contact with Susannah Taylor’s children after their mother’s death in 1823, although the lack of extant correspondence after 1804 is curious.

In Three Generations of Englishwomen, Ross transcribes a brief section of a letter which suggests that Taylor had little patience with Opie’s fondness for London and the company she kept there: “‘Dr. Alderson,’ she writes, ‘[read] me some letters of Mrs. Opie’s, which completely prove that the whole fraternity of authors, artists, lecturers, and public people get such an insatiable appetite for praise, that nothing but the greatest adulation can prevent their being miserable’.”11 In 1807, Taylor sent news of John Opie’s death and expressed concern for the new widow: “You know what I feel for my dear friend, what will be its effect upon her I can scarcely guess, but I think quite overpowering for a long time.” 12A few years later, Taylor mentions that during a visit to London, “Mrs. Opie treated me with her company three hours last night. She read me some charming songs she had been writing, and was quite herself.” 13 Taylor’s qualification of Opie suggests that her friend was not always “herself” during this period, which was when Opie was most consumed with fashionable London society and cultivating the persona of a literary “lioness.” Ironically, Opie’s own sense of growing distance from Taylor dates to about a decade later, after her return to devout Christian piety. In a letter to Joseph John Gurney written in February 1823, Opie laments that Taylor, seriously ill and near death, seemed intent upon “a sort of Heathen philosopher’s death . . . [she] talked of ‘Providence’ and of it pleasing God to do so and so, but du Sauveur pas un mot.”14

However this great friendship ended, its beginnings were instrumental in the development of Opie as a writer. Furthermore, the letters written to Taylor document the personal:love affairs with Robert Batty and John Opie; the literary: Opie’s interactions with the Godwin-Wollstonecraft circle; and the political: her radical leanings and the volatile

climate during the Treason Trials. As such they remain invaluable documents allowing us to position Opie within the vibrant social networks of early nineteenth-century London.15

1. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) spells Taylor’s first name “Susanna,” however, all biographers since her great-great-granddaughter Janet Ross,

have added an “h”. Opie’s letters address her familiarly as “friend” in opening salutations and the address label identifies her as “Mrs. John Taylor”.

↩

2. Opie writes of singing Taylor’s song, “The Trumpet of Liberty,” in a letter to Taylor written in October of 1794.↩

3.Several prominent Victorian women writers, including Harriet Martineau, Elizabeth Rigby, Lady Eastlake, and Taylor’s own daughter and granddaughter

(Sarah Austin and Lady Duff Gordon) are descended from these Norwich families.↩

4. Amelia Alderson [Opie] to Mary Wollstonecraft, Oxford, MS. Abinger c. 41.↩

5. Janet Ross, Three Generations of Englishwomen, John Murray, 1888, 39.↩

6. Ross, Three Generations of Englishwomen, John Murray, 1888, 16-17.↩

7. Ross, Three Generations of Englishwomen, John Murray, 1888, 13. Susannah and John’s

children met with notable success as adults. All but two of their seven children have entries in the ODNB. John (1779-1863) was a mining engineer and a

member of the Royal Society; Richard (1781-1858) founded the printing company now known as Taylor and Francis; Edward (1784-1863) was a professional musician, translator of German music,

and the Gresham Professor of Music; Philip (1786-1870) was a civil engineer; and Sarah Taylor Austin (1793-1867) became a well-known writer and translator. Susan (1780-1814) married Henry

Reeve, a medical writer and physician, and Arthur (b. 1790) worked with Richard in the printing business.↩

8. Ross, Three Generations of Englishwomen, John Murray, 1888, 9.↩

9. Ross, Three Generations of Englishwomen, John Murray, 1888, 4.↩

10. Ross, Three Generations of Englishwomen, John Murray, 1888, 42.↩

11. Ross, Three Generations of Englishwomen, John Murray, 1888, 27.↩

12. Ross, Three Generations of Englishwomen, John Murray, 1888, 37.↩

13. Ross, Three Generations of Englishwomen, John Murray, 1888, 43.↩

14. Amelia Opie to John Joseph Gurney, February 11, 1823, Friends Library Gurney mss. 1/336.↩

15. In addition to the above sources, I have referred to the following works when compiling this critical introduction:

Isabelle Cosgrave, “Untrustworthy Reproductions and Doctored Archives: Undoing the Sins of a Victorian Biographer” in The Boundaries of the Literary Archive: Reclamation and Representation, Ashgate, 2013, pp. 61-74;

Ann Farrant, Amelia Opie: the Quaker celebrity. JJG Publishing, 2014;

Harriet Guest, Unbounded Attachment: Sentiment and Politics in the Age of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 2013;

Shelley King and John Pierce, eds., The Collected Poems of Amelia Alderson Opie, Oxford University Press, 2009; and Jon Mee, Conversable Worlds: Literature, Contention, and Community, 1762-1830. Oxford University Press, 2011.↩